Willing Slaves

Slavery wasn't a white invention—it's human depravity. From African kingdoms to modern victimhood, the chains have changed but bondage remains.

There's a bondage worse than that of chains and shackles. It's the yoke you defend, the tether you see as freedom, the cage you mistake for a castle.

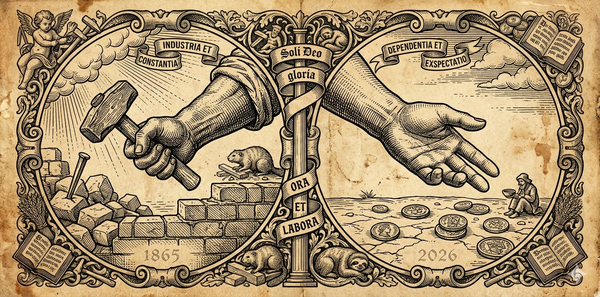

History offers us an uncomfortable truth: the institution of slavery didn't begin in 1619, didn't originate in America, and didn't end when the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified. What did end in America—at least in its physical form—is the legal right to own another human being. But slavery itself? This ancient evil predates European colonialism by millennia and continues today in various forms across the globe. To understand this is to grasp a fundamental reality about human nature: we are all enslaved to something. The only question is what—or more precisely, to whom.

The thought seed that sparked this reflection is blunt: "If you wouldn't have been a willing slave worker, then don't be a willing slave voter." It's a provocative notion, and intentionally so. Because if there's one thing more insidious than the physical bondage, it's ideological bondage—the kind where the enslaved not only accept their chains but argue passionately for them.

The Historical Record

Let's establish some uncomfortable facts. Slavery was not invented by white Europeans. It was not unique to the transatlantic slave trade, and it was not exclusively a matter of Europeans enslaving Africans. The historical record is far more complicated than the simplified narrative would lead us to believe.

Consider Anthony Johnson. He arrived from Angola around 1624—not as a free man, but as a slave. He was sold to a merchant as an indentured servant and gained his freedom about a decade later, receiving land and a cow in 1651. Johnson then did something that disrupts the tidy racial binary: he bought more land and acquired his own indentured servants, including at least one black servant. Johnson wasn't an anomaly; he was an illustration of a broader truth—slavery was an economic and power-driven institution, not fundamentally a racial one.

African kingdoms like the Dahomey and Ashanti built substantial wealth on the slave trade long before European ships arrived on their shores. Arab and Muslim slave trading predated 1619 by centuries and, in some regions, hasn't stopped. To frame slavery as exclusively a white-on-black American phenomenon is not just historically inaccurate; it's a convenient lie that serves a specific narrative agenda.

Making slavery about race lets everyone off the hook except white Americans. Recognizing that it's really about human depravity forces all of us—regardless of our melanin content—to reckon with our capacity for evil. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn captured this when he wrote, "The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either—but right through every human heart."

The Modern Plantation

Here we arrive at the heart of the matter: if chattel slavery ended in America, why do its descendants seem so determined to remain mentally enslaved? And more provocatively—to what do they continue to be enslaved?

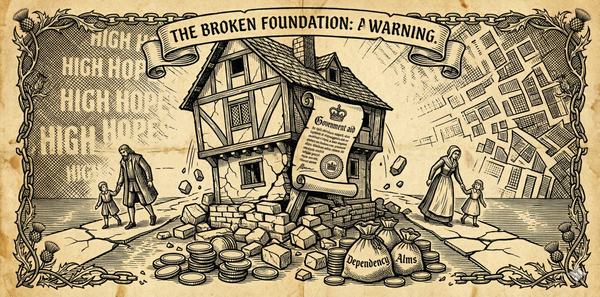

The answer, I hesitate to say, is victimhood. But not just victimhood as a personal disposition; victimhood as an entire industry. There's a term for this: the professionalization of grievance. It's the machinery that benefits enormously from perpetual racial tension and dependency—not because it solves problems, but precisely because it doesn't.

Here's the uncomfortable parallel: black ancestors who were physically enslaved didn't demand reparations. They focused on literacy, property ownership, business creation, and building institutions. They were, by and large, oriented toward the future, not fixated on payment for the past. But their descendants, 160 years removed from slavery's abolition, can't seem to stop talking about what they're owed. What changed?

The people closest to the wound focused on healing and building. The people furthest from it keep picking at the scab. That's not justice; that's industry. And the question we must ask is: who profits from this perpetual grievance? Certainly not the supposed victims.

All Humans Are Enslaved

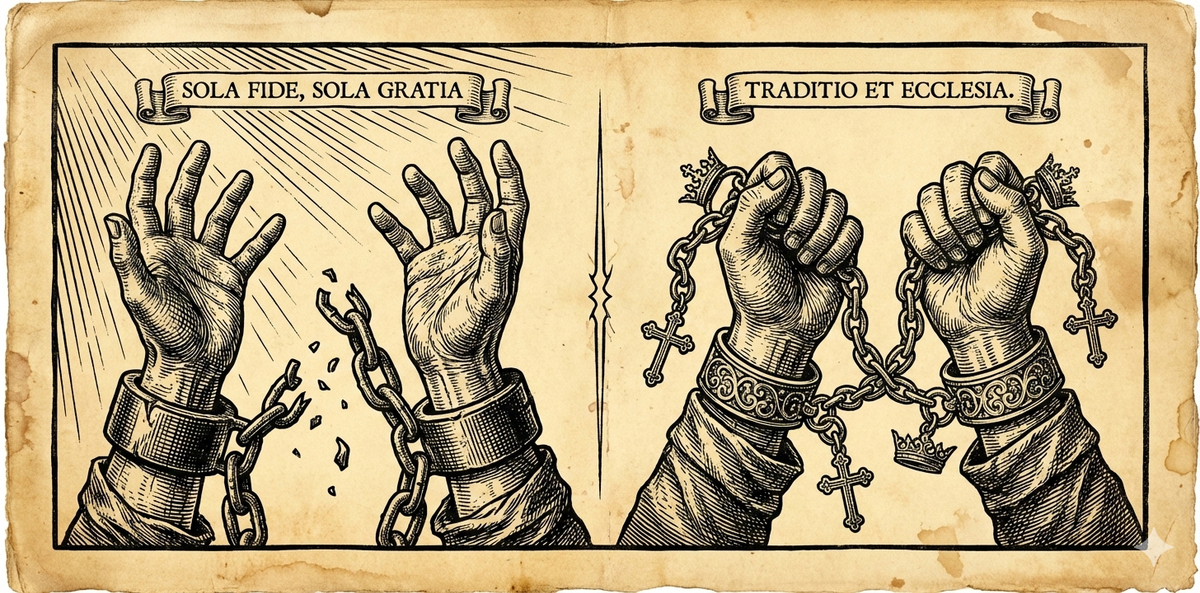

Here's where theology enters the conversation, because the Christian worldview has something essential to say about human nature and freedom. In a Reformed understanding of Scripture, all humans are enslaved to something. Believers are enslaved to Christ—and yes, that language is intentional. We are literally Christ's bondservants, His slaves ("duoloi" the Greek). This is not the only way our relationship to Christ is described, but it is one undeniable facet of that reality.

For unbelievers, the bondage is to the flesh, to sin, to systems of thought that promise liberation but deliver only stronger chains. This isn't metaphorical; it's the actual state of the unregenerate human will. So, while we may choose our masters, we certainly don't choose whether or not to have one.

The irony, then, is profound: descendants of people who fought desperately to escape physical slavery now willingly embrace ideological slavery. They defend the very narratives and political dependencies that keep them bound. They mistake the plantation for empowerment, the chains for compassion.

The Inconvenient Truth

If you're convinced you're a victim, then you are your own victimizer. Victimhood is a cage disguised as compassion. It's a form of slavery that doesn't require overseers because the enslaved police themselves—and each other. Diverge from the approved narrative, and you'll discover how quickly the "skinfolk" become enforcers of ideological conformity.

The greatest disrespect to enslaved ancestors is to squander the very freedom they never had. They had the will but no way. Their descendants have a way now but no will. Instead of acting out of our intelligence, there's an industry built on acting out of our ethnicity. Instead of building on the foundation their forebears laid, society's cry is to keep paying for sins long since atoned for—if not spiritually, then certainly legally and culturally.

Slavery as it existed in America is gone. It ended here before it ended in many other parts of the world—and for a comparatively short time. It ended not because of global consensus but because of a bloody civil war and a constitutional amendment. And yet the narrative persists that America is uniquely guilty, uniquely oppressive, uniquely racist. This is not history; it's mythology in service of ideology.

The Better Master

I close with this: if all humans are enslaved to something, the question isn't whether you'll serve, but whom. Physical chains are obvious; ideological chains feel like compassion, like empowerment, like justice. That's what makes them so insidious.

The old slaves knew their bondage and sought freedom. Their descendants seem content to exchange one form of slavery for another—and to call it progress. That's not liberation. That's a con. And the saddest part? The supposed beneficiaries aren't the ones profiting from it.

Slavery didn't start with America, and it didn't end with America. But what did end in America—at least in its legal, physical form—was the right of one human to own another. The question now is whether Americans, especially those whose ancestors bore that burden, will reject the mental and ideological slavery being offered in freedom's clothing.

The masters have changed. The chains have too. But the truth remains: if you would not have been a willing slave worker, don't be a willing slave voter. Bondage is still bondage—no matter how it's packaged.