The Reparations They Never Demanded

The freedmen who endured slavery focused on building, not demanding reparations. Their descendants do the opposite. What changed?

It's interesting how almost none of the newly freed slaves demanded reparations for their enslavement.

Think about that for a moment. The people who actually endured slavery—who bore the whip marks, who knew what it meant to be property, who walked out of bondage with nothing but the clothes on their backs and whatever tools they could carry—these people didn't obsess over what they were owed. They looked forward. They built schools. They bought land. They started businesses. They reunited families torn apart by auction blocks.

Their descendants, 160 years removed from the last legal slave sale in America, can't stop talking about reparations.

What changed?

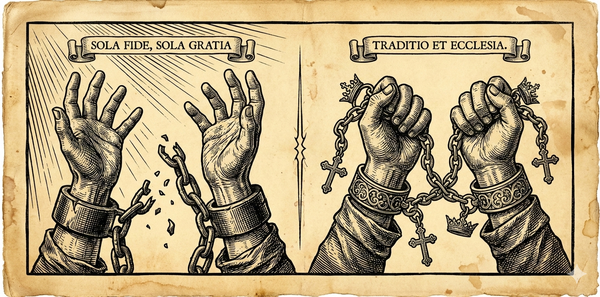

The Freedmen's Choice

It's not wholly accurate to lionize the freedmen as if they achieved some saintly transcendence above their plight. They were human beings, after all, with all the flaws and failings common to us all. Many of them still smarted over the scars they felt from the whips of their masters. And let's be clear: those were real harms done against real people by real people.

But they had the sense to know that if they took what they'd been given—their emancipation from slavery—and if they worked hard at it, they could make something of themselves. They could rise up. I've no doubt they inherited this outlook from their own masters who had extensive land holdings were likely (many, at least) very diligent, hardworking stewards of their holdings.

These freedmen had watched. They had learned. And they capitalized on those lessons. The more observant ones doubtless inheriting a strong sense of their own "manifest destiny."

Within a generation, black literacy rates climbed from near zero to over 50%. Black-owned businesses sprang up across the South. As I documented in my examination of the Great Society's impact, entire neighborhoods—Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Sweet Auburn in Atlanta, Jackson Ward in Richmond—became economic engines. Historically black colleges and universities trained doctors, lawyers, teachers, and ministers. The black church became the anchor of community life, moral formation, and mutual aid.

Was progress slow? Yes. Was discrimination still rampant? Absolutely. Were there setbacks along the way—violent, unjust setbacks? Absolutely. But the trajectory was unmistakable: upward, forward...building, not begging.

Booker T. Washington captured this spirit when he spoke of "the cessation of bitterness" and the acknowledgment of real progress. He wasn't denying past injustice; he was refusing to let it define the future. He understood what the freedmen understood: grievance is cheap, but construction, though costly in effort, is of far greater value.

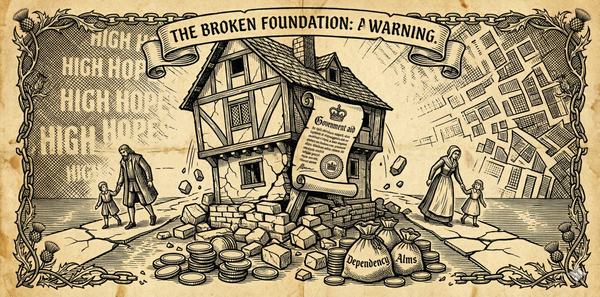

The Professionalization of Grievance

Fast-forward to today, and you find something quite different. Not the people who endured slavery, but those furthest removed from it, convinced that their life problems will be solved by some fat reparations check.

It really is quite sad that people are inclined toward grievance. Human nature is, in point of fact, predisposed toward finding entitlements where they don't exist, finding cause for complaint where it doesn't exist, finding someone on whom to saddle our own responsibilities. I'm broke, so I want to blame the man or the system or the economy or the current political regime.

These are sentiments—whether perceived or actual—that are exploited by the same ideological machinery personified in figures like Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton and Shaun King, and the list (sadly) goes on. Some of these older voices have spawned many ideological progeny who continue the work of capitalizing on this version of outrage culture. Their shared goal: to make merchandise of such overwrought and under-informed sentiments.

Ask yourself: who benefits from perpetual victimhood? Not the supposed victims. The race hustlers and race baiters who stoke these flames—they're the ones building empires on resentment. They're the ones who need black Americans to believe they're owed something they can never quite collect, because the moment that debt is "paid," their industry collapses.

The people closest to the wound were focused on healing and building. The people furthest from it keep picking at the scab. That's not justice—it's business.

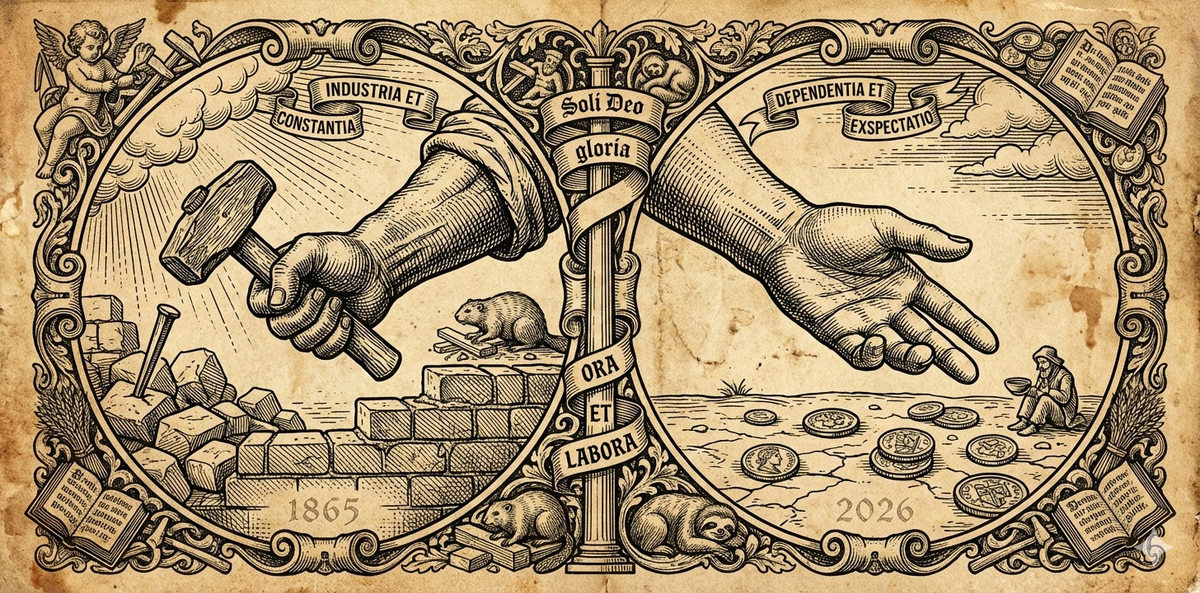

The Old and the Young

"The old had the will but no way; the young have a way but no will."

That line haunts me because it's so precisely true. The freedmen had every reason to demand reparations and precious little means to secure them. Their descendants have every means to secure prosperity and precious little will to pursue it with diligence.

It's easy to complain about oppression from an air-conditioned spot on the sofa. That's a far cry from the freedmen walking many miles barefoot, dwelling in shabby shacks, working fields that would one day become their own. The world, regardless of anyone's deserving it, has given the folks of today multiple layers of affluence: technologies, labor-reducing devices, life-saving infrastructure. They're no longer walking miles barefoot—they're flying along in cars loaded with luxury.

And yet, many of them, driven by their own sin nature, have decided to side with the grievers. They jump into rioting whenever there's some decision made by local government that goes against a perceived group (the Minneapolis drama comes to mind). It's the path of least resistance combined with the whole Lord of the Flies instinct: let's go for ours at the expense of others because, after all, it's owed to us.

If you're convinced you're a victim, then you are your own victimizer.

What the Record Shows

Look objectively at our culture and you'll find no shortage of factual, verifiable evidence that we have progressed so far that our so-called race grievance proves baseless and irrelevant. Legal segregation is dead. Discrimination is illegal. Affirmative action policies have been enforced for decades. A black man served two terms as President of the United States.

None of this negates individual instances of racism or injustice. But it does negate the claim that America in 2026 owes a collective debt for slavery that ended in 1865.

The freedmen understood something their descendants have all but forgotten: you can't build a future on the foundation of past grievances. You can acknowledge wrong, work toward justice, and still move forward. That's what they did. They took their emancipation and made something of it—not because they were superhuman, but because they refused to let bitterness consume what little opportunity they had.

Reflection

I think even in the smoldering ashes of slavery, when the freedmen first took their first steps toward independence and self-establishment, they understood a basic truth: the only person who can truly hold you back is yourself.

The reparations they never demanded weren't a sign of weakness or submission. They were a sign of wisdom. They knew that waiting for the world to make things right would leave them waiting forever. So they got to work.

Their descendants would do well to remember that.

Because the people who actually suffered slavery didn't have time for grievance politics. They were too busy building.