Tribal Temptation

A Christian reflection on the temptation to weaponize state power against political enemies—and why principled restraint is harder than it looks.

I confess: the temptation is real.

When evidence mounts of the previous administration's weaponization of government agencies—the "debanking" of political opponents, the cozy collusion between federal bureaucrats and social media platforms, the selective prosecution that would shame a banana republic—I find in myself an urge to cheer every counterstrike. Let the new regime wield the same instruments against their enemies. Let them taste their own medicine. The moral outrage issuing from the populist wing of my political tribe (and make no mistake, I stand closer to that wing than to the establishment alternative) is not unfounded; it is, in many respects, well-founded. The abuses were real. The censorship apparatus was real. The two-tiered justice was real.

And yet.

The Christian finds himself, or ought to find himself, in an uncomfortable position: sympathetic to the grievance, wary of the remedy. From time to time—thankfully—I am reminded of the necessity to resist such temptation and to restrain such urges. Not because the grievances are illegitimate, but because the soul that luxuriates in righteous anger has a way of becoming something other than righteous.

The Case for the Sword

I should confess something else: I am no pacifist about political power.

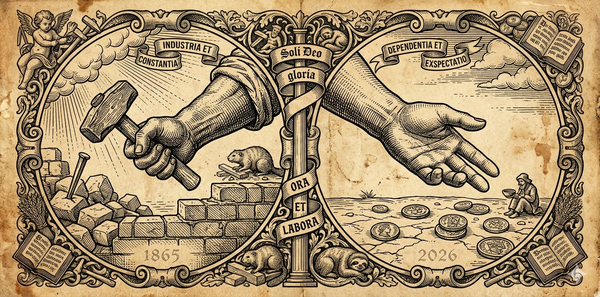

I'm a devoted listener of several right-leaning media voices—Matt Walsh's cultural bulldozer approach has its appeal, but it's Michael Knowles whose prolific intellectualism really resonates. I'm something of a sucker for thinkers who are also great articulators; if you will, I prefer my polemics literate. Knowles has been known for advocating precisely this: wielding power in the new school way against those who have wielded it from the opposite end of the spectrum, accelerating our culture's decay and degradation. And on some level—I will not pretend otherwise—I agree with this. Power is not a neutral tool that only becomes corrupted when conservatives touch it. The left understood this decades ago; the right is only now catching up. To refuse to govern when you have the mandate to govern is its own form of moral abdication.

I will not here make a complete case against this posture. It deserves a fuller treatment than I can offer in these few paragraphs.

But I would offer strong cautions.

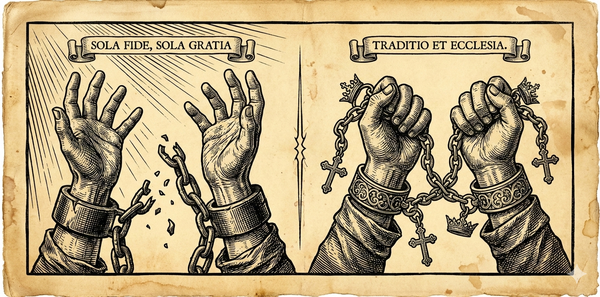

As an aside—and I offer this tentatively, since I would not presume to impugn a man's character by asserting what I cannot verify—I suspect Knowles's slightly more aggressive posture may be attributable, at least in part, to his Roman Catholicism. The Catholic tradition has historically been less squeamish about the exercise of temporal power in service of divine ends; the Protestant tradition, particularly the Puritan strand in which I stand, has been more suspicious of entangling the sword with the Spirit.

Though I should be honest: my own heritage is not purely one of principled quietism. I am also influenced by the more militant Huguenots—those French Protestants who, when faced with annihilation, concluded that self-defense was not incompatible with faith. Therein lies a tension I have not fully resolved, and I doubt I am alone in this.

That notwithstanding, I find it safe to regard Catholics like Knowles as co-belligerents on many key fronts—on the sanctity of life, on the objective reality of truth, on the necessity of resisting the cultural slide into moral incoherence. Francis Schaeffer coined the term for precisely such alliances; it remains useful. But co-belligerency is not identity. And I suspect the place where our instincts diverge—where the Puritan in me parts company, however slightly, with the Catholic posture—is precisely here: at the question of how eagerly one reaches for the temporal sword.

When Restraint Looks Like Betrayal

Consider the recent positioning of Mike Pence—not as political endorsement, but as illustrative specimen.

When FCC Chairman Brendan Carr publicly threatened ABC with regulatory consequences over Jimmy Kimmel's commentary regarding conservative activist Charlie Kirk, Pence took a curious position. He called Kimmel's remarks "crass" (they were). He affirmed ABC's right as a private employer to fire him (which it has). And yet he criticized the FCC's intervention: "I would have preferred that the chairman of the FCC had not weighed in."

For this measured stance, Pence has been labeled a collaborator with the very censorship regime his party seeks to dismantle. The accusation is not that he did something wrong; it is that he refused to use the sword when it was offered.

This is the logic of the tribal moment: restraint equals complicity. If you will not punish our enemies with the instruments of state, you must secretly be one of them. The fact that Pence traveled to Chatham House in London and publicly criticized the UK government for "imprisoning citizens for what they say or pray" carries no weight in this calculus. The fact that he maintains what can only be described as a First Amendment absolutist position—incompatible with British Labour's "safety-first" approach to speech—is irrelevant. He did not swing when swinging was possible; therefore, he is suspect.

The Founders' Ghost

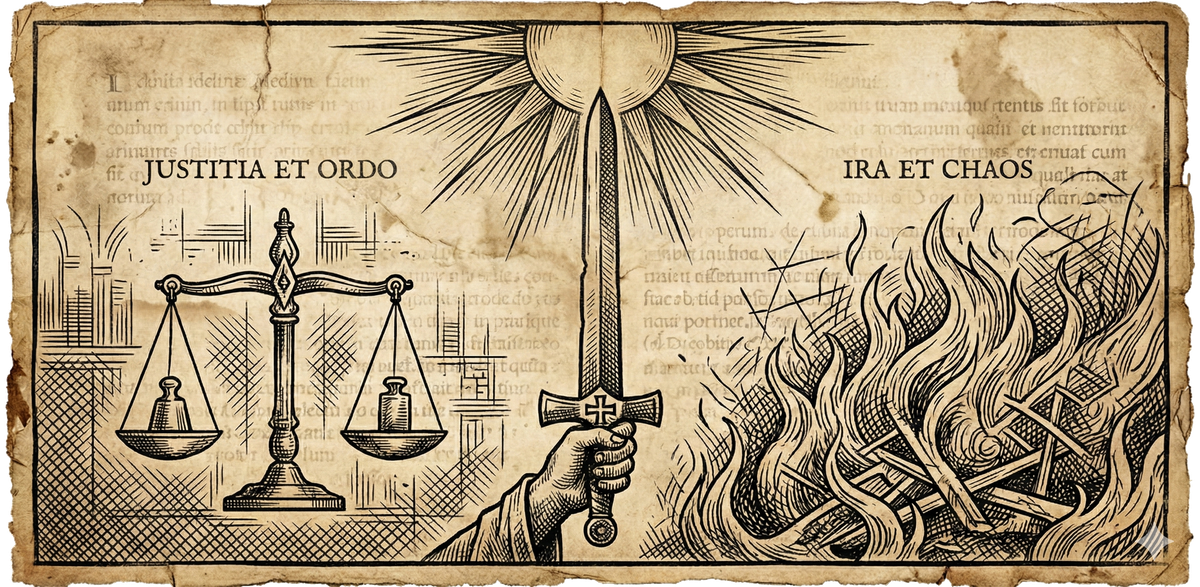

The irony—and it is a bitter one for those of us with classical liberal sympathies—is that this logic inverts the entire American constitutional project.

"Constraint, constraint, constraint"—that was the overriding obsession of the Founders. The Whig tradition that shaped our constitutional order was predicated on a profound suspicion of concentrated power, even when your own faction wields it. Madison's observation that "if men were angels, no government would be necessary" cuts both ways: it applies equally to the bureaucrats you despise and the populists you applaud. The whole point of separation of powers, of enumerated rights, of a Bill of Rights that exists precisely to limit what government may do even when majorities demand otherwise—all of this presupposes that your side, too, is capable of tyranny.

The temptation to weaponize the state is not new. What is new—or newly articulated—is the open abandonment of principled restraint as a virtue. The populist logic runs: they did it first, so now it's our turn. And there is something emotionally satisfying about this. But emotional satisfaction is not the same as moral wisdom.

The Christian's Dilemma

The line between justice and revenge is notoriously thin, and the Christian has been warned about precisely this conflation.

"Vengeance is mine," says the Lord (Romans 12:19)—not because vengeance is wrong in itself, but because we are disqualified from executing it impartially. Our justice has a way of becoming mobstice; our righteous anger, a convenient cover for tribal score-settling. The magistrate does not bear the sword in vain (Romans 13:4), but the magistrate is not you—and even the magistrate operates under divine constraints that transcend partisan advantage.

How does the Christian distinguish between legitimate assertion of authority and tribal vengeance masquerading as justice? The answer, I suspect, involves something like this: the posture of the heart matters as much as the policy outcome. Are we pursuing justice because it honors God's design for ordered society—or because we want to watch our enemies suffer? That is a question each of us answers privately, before an Audience of One.

A Final Word

I do not know whether Pence is right on the merits of the Kimmel incident. I am not here to adjudicate his political future or to endorse his candidacy for anything. But I know this: the instinct that reads principled restraint as secret treachery is an instinct I must discipline in myself.

The abuses of the previous regime were real. The desire for accountability is legitimate. But the Christian—and, indeed, the classical liberal—must ask a harder question than "Were we wronged?" The harder question is: "What kind of people do we become in the pursuit of redress?"

When the whole world is running toward the cliff, wrote C.S. Lewis, he who runs in the opposite direction appears to have lost his mind. Perhaps. But the cliff remains a cliff, regardless of which direction the mob is running.

The tension, I suspect, will be with me for a while yet.