The Unrelenting Ghetto

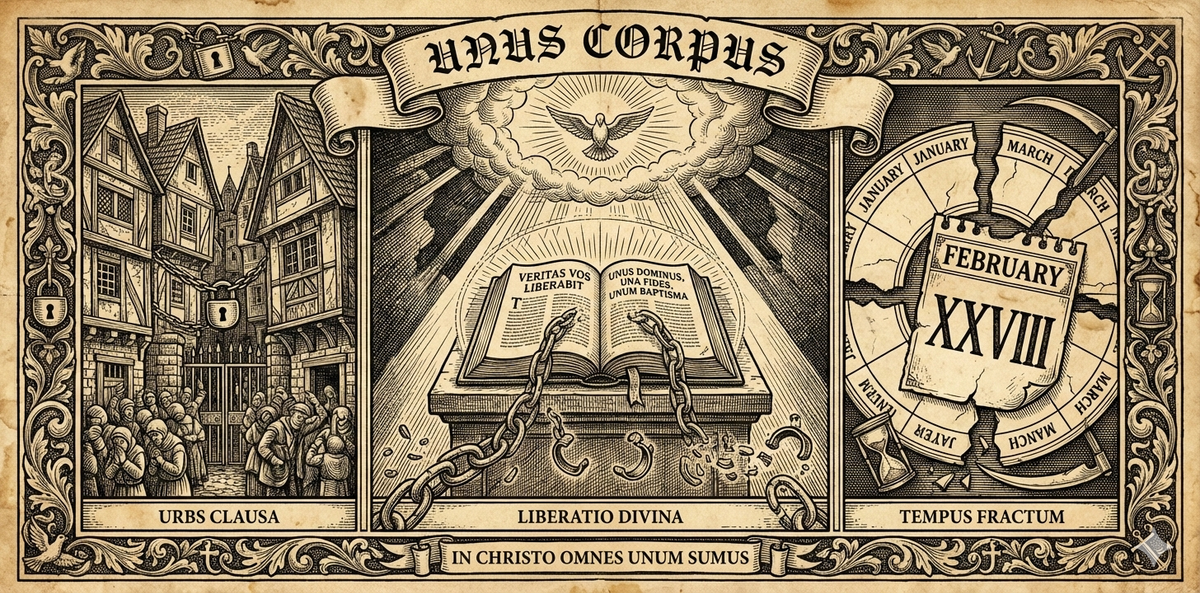

The ghetto promises care while delivering containment—whether housing projects, Black History Month, or black theology. True honor integrates; it doesn't segregate.

The ghetto always promises care while delivering containment.

That's the thread connecting three seemingly unrelated phenomena: Great Society housing projects, Black History Month, and the black theology class I took back in college. Each emerged from good intentions—efforts to overcome past ills, repair past damages, address legitimate grievances. And each, in its own way, ended up building walls where bridges were needed.

The ghetto doesn't always look like crumbling high-rises and broken elevators. Sometimes it looks like a calendar designation or a college syllabus. But the mechanism is the same: separate the thing you claim to honor, call that separation "special treatment," and congratulate yourself for showing you care.

The Physical Ghetto: When Help Hindered

The Great Society's housing initiatives were supposed to lift black families out of poverty. Instead, they concentrated poverty and called it compassion. I've written elsewhere about how these programs—with their perverse incentives that penalized marriage and rewarded fatherlessness—didn't eliminate the ghetto but institutionalized it.

What began as emergency intervention became permanent infrastructure. The projects weren't stepping stones; they were holding pens. Generations grew up in spaces designed for temporary relief but administered as permanent containment. The help that was supposed to be a hand up became a hand out.

This is what well-meaning paternalism does: it addresses symptoms while entrenching causes. It provides housing while destroying homes. It offers material assistance while eroding the social structures—marriage, family, community accountability—that actually lift people out of poverty.

The Temporal Ghetto: February's False Favor

Morgan Freeman asked the question nobody wanted to answer: why does black history get relegated to the shortest month of the year?

His point wasn't calendrical nitpicking. It was philosophical dynamite. Segregating "black history" into its own designated month implies it's not already integral to American history. The very framing perpetuates the otherness it claims to remedy.

When I first heard Freeman's comment, what clicked wasn't just agreement—it was recognition. There's no real philosophical need to show younger generations that black people require some distinct spotlight, as if they're either so exceptional they rise above their white counterparts, or so victimized that their achievements must be framed as superhuman feats accomplished despite white oppression.

We're long past the point where that needs to be the emphasis. Just include whoever's heritage and legacy and contributions warrant inclusion. Make it seamless. Make it practically indistinguishable from the broader American story—because that's exactly what it is.

Black history is American history. Booker T. Washington belongs in civics courses, not corralled into February. Bass Reeves belongs in law enforcement history. Robert Robinson Taylor belongs in architecture curricula. George Washington Carver belongs wherever we teach agricultural science. Their stories aren't addendums to the American narrative; they are the American narrative.

February ghettoizes what should be woven throughout. It's easier to dedicate a month than to do the harder work of genuine integration—actually teaching these figures year-round, in context, as full participants in the nation's story rather than special guests trotted out for twenty-eight days of performative acknowledgment.

True honor doesn't segregate. It integrates.

The Theological Ghetto: When the Gospel is Gagged

Then there's the ghetto I walked into voluntarily: Dr. Leonard Lovett's black theology class at a well-known charismatic university.

I don't remember much of the curriculum in detail. What I do recall is the atmosphere—steeped in some perceived ethos of blackness and how it supposedly finds affirmation in Scriptural principles. It was heavily drenched in sociology and black liberation thinking.

Here's the problem: that corpus of thought cannot be objectively derived from Scripture. It's a separate ideological framework linked loosely to certain biblical principles, but indefensibly so. Black theology, as I encountered it, didn't apply the gospel to the black experience. It subordinated the gospel to racial identity—making melanin the interpretive key rather than Christ.

If black history is American history (and it is), then "black theology" as a distinct discipline is as incoherent as "left-handed theology" or "tall-person theology." There's just theology—the study of GOD and His revelation—applied to all contexts, all people, all times. The moment you carve out a racially-specific theological category, you've ghettoized the very gospel that breaks down every dividing wall.

The civil rights movement rightly appealed to Acts 10:34-35: "GOD is not one to show partiality." That's a universal axiom; GOD who made all people does not see or treat them differently based on skin color or any other man-made distinction. But too often, those who invoke this truth then undermine their own argument by making a case for why black people should receive special treatment. That's self-refuting. You can't appeal to divine impartiality while demanding human partiality.

The body metaphor in 1 Corinthians 12 offers the alternative: diversity within unity. Different members, different functions, one body. The eye doesn't demand a separate "eye theology." The hand doesn't insist on its own interpretive tradition. Each part serves the whole, complementing the others, working together in holistic fashion—proclaiming the gospel above all earthly matters.

The ghetto—whether spatial, temporal, or theological—always promises care while delivering containment. It separates what should be integrated. It spotlights what should be seamlessly included. It honors with one hand while denigrating with the other.

Christ didn't come to build better ghettos; He came to break down dividing walls (Ephesians 2:14). The church He's assembling—the church universal, the church militant, His hands and feet to an unregenerate world—isn't organized by melanin content. It's organized by calling. Different gifts. Different functions. One body. One LORD.

The solution to historical segregation isn't new forms of segregation with better marketing. It's actual integration: including the names worth naming, telling the stories worth telling, teaching the theology worth believing—not as separate categories, requiring special months or special disciplines, but as part of the seamless whole.

Period, paragraph, page.