Righteousness and Peace Have Kissed

Psalm 85:10 reveals the Incarnation's impossible math: how God's righteousness and mercy meet in Christ. Not sentiment but surgical precision.

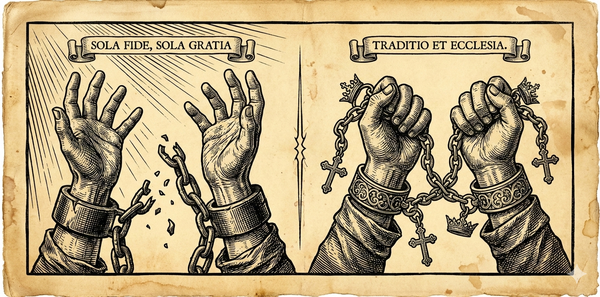

There is a verse tucked into the Psalms—Psalm 85:10, to be precise—that renders in six words what theologians have spent centuries trying to unpack: "Mercy and truth are met together; righteousness and peace have kissed each other." A kiss. Not a handshake, not a formal treaty signing, not even a reluctant truce. A kiss—just about the most intimate thing two entities can do with one another, barring any actual sexual activity. And what's being reconciled here? Two things that, by all reasonable human calculation, should remain in violent opposition: the righteousness of God and the peace He offers to undeserving rebels.

Really, when I think about a kiss, I think of intimacy distilled to its most physical, most vulnerable expression. It is not merely symbolic; it is enacted proximity. And so when Scripture employs this imagery to describe the meeting of divine righteousness and divine mercy, we are confronted with the most poignant of contrasts synthesized into the most poignant of embraces. One could not be clearer in trying to illustrate the reconciliation of two erstwhile contradictory—even violently opposed—realities.

The righteousness of God is particularly noteworthy because it is so much higher, greater, deeper, richer, and immeasurably beyond any notion of righteousness that man on his own can achieve. This is not the self-congratulatory moral scorekeeping we practice in our daily lives ("Well, at least I'm better than that guy"). This is the kind of righteousness that burns like a consuming fire, that cannot tolerate even the shadow of sin, that demands absolute perfection or absolute judgment. Conversely, the mercy of God exceeds—in all those same metrics—anything we are capable of expressing to one another. Our mercy is conditional, limited, and usually self-serving. God's mercy is sovereign, infinite, and terrifyingly costly.

So on the one hand, I think about how absolutely holy and just the Lord is. On the other hand, I think about how absolutely inclined toward mercy He is. And then when I look at this imagery of the kiss, my mind is boggled. I'm dumbfounded by how a God could condescend so profoundly in drawing man to Himself and placing him in right relationship to Himself. It underscores the reality that this is a divine work, born of divine initiative, accomplished by divine effort—through no meaningful effort on the part of the human who is the unworthy and undeserving recipient thereof.

The Incarnation: Where Impossibility Becomes Flesh

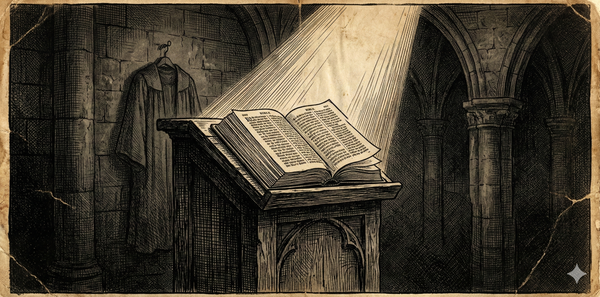

The Incarnation is where Psalm 85:10 stops being poetry and starts being history. Christmas—stripped of its tinsel and sentiment—is the moment when God's righteousness and God's peace meet in the person of Jesus Christ. The God-man (not "divine person," not "spiritual entity"—God incarnate in human flesh) is the kiss made physical. In Him, mercy and truth converge. In Him, righteousness and peace are no longer at war.

This is not "good news" in the casual sense we throw that phrase around when the grocery store has a sale or the weather forecast looks favorable. This is the greatest news, to an extent hard to describe with any real accuracy. It is ontological restructuring. It is the answer to an equation humanity has been fumbling with since Eden: How can a holy God reconcile sinful man without compromising His holiness or annihilating His creation?

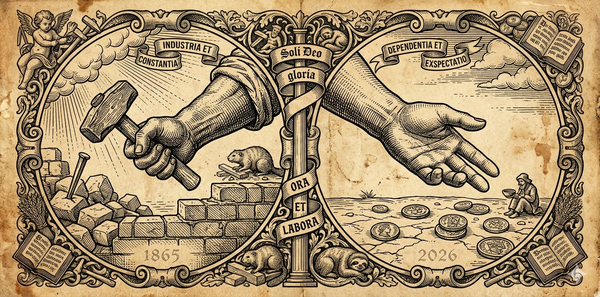

The answer is not found in man's effort. It is not found in human worth or inherent goodness (we have none). The answer is found in God doing what only God can do: stepping into the mess, absorbing the cost, paying the price His own righteousness demands. The Incarnation is not God lowering His standards; it is God meeting His standards on our behalf.

Micah's Blueprint: What God Requires, Christ Provides

Micah 6:8 offers what might be the most succinct summary of divine expectation in all of Scripture: "He has shown you, O man, what is good; and what does the LORD require of you but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God?" Three simple directives. Act justly. Love mercy. Walk humbly.

Simple, perhaps—but not easy. In fact, they're impossible. Not difficult-but-achievable-with-enough-willpower impossible, but actually, genuinely, ontologically impossible for fallen human beings. We are congenitally incapable of doing justice without self-interest, loving mercy without condescension, or walking humbly without pride sneaking in through the back door. (Even our humility, if we achieve it, becomes a source of pride. We are wretches all the way down.)

This is where the Incarnation reveals its genius. Christ fulfills Micah 6:8 perfectly—acting justly, loving mercy, walking humbly—on our behalf. He does what we cannot do, then offers it to us as a gift. God doesn't just demand righteousness; He becomes it, then credits it to our account. The kiss between righteousness and peace isn't metaphorical theology; it's the lived reality of Jesus Christ, who embodies both.

The Cultural Blind Spot: Downplaying Undeservedness

I know this may sound kind of heady theologically, but it really does strike at the very heart of the gospel's compelling nature, its mind-bogglingness, its beauty. And here's where I think the cultural church has a massive blind spot: it emphasizes too much man's own effort, man's own inherent worth. It does not wrestle through—or even attempt to address sufficiently—the reality that man is simply undeserving.

That undeservedness is just as stark, just as extreme, as the mind-boggling generosity of God's divine initiative. We want to soften the blow, to preserve some shred of human dignity in the transaction. We talk about God "meeting us halfway" or "seeing potential in us" or "loving us for who we are." These are sentimental half-truths at best, and damnable lies at worst. God does not meet us halfway; He comes the entire distance while we are still enemies. He does not see potential in us; He sees ruin and rebellion. He does not love us "for who we are"; He loves us in spite of who we are, and He changes who we are by the sheer, benevolent force of His sovereign will.

The kiss between righteousness and peace is not a romantic gesture between equals. It is the incomprehensible condescension of a holy God toward creatures who deserve nothing but wrath. And if that reality doesn't leave you staggered—if it doesn't render you speechless with gratitude and dread—then you haven't understood it yet.

The Heart-Rending Reality

The gospel is not merely a good story. It is not a feel-good narrative designed to boost our self-esteem or validate our choices. It is—to an extent hardly describable—the greatest news. It is the monumental announcement that the impossible has been accomplished, that the equation has been solved, that the kiss has occurred. Righteousness and peace are no longer at odds because Christ has reconciled them in Himself.

Christmas, rightly understood, is not about warm feelings or family gatherings or charitable giving (though these may accompany it). Christmas is about God invading human history to do what we could not do for ourselves: satisfy divine justice while extending divine mercy. It is about a God who refuses to lower His standards but chooses instead to meet them Himself, at infinite cost, for the sake of rebels who did nothing to deserve it.

It is because God wrote the terms, paid the price, and accomplished the covenant He alone could fulfill. All that remains for us is this: either we continue in the natural rebellion of our dead hearts, or—by grace alone—God awakens us to embrace what we could never earn. "Awake, O sleeper, and arise from the dead, and Christ will shine on you."