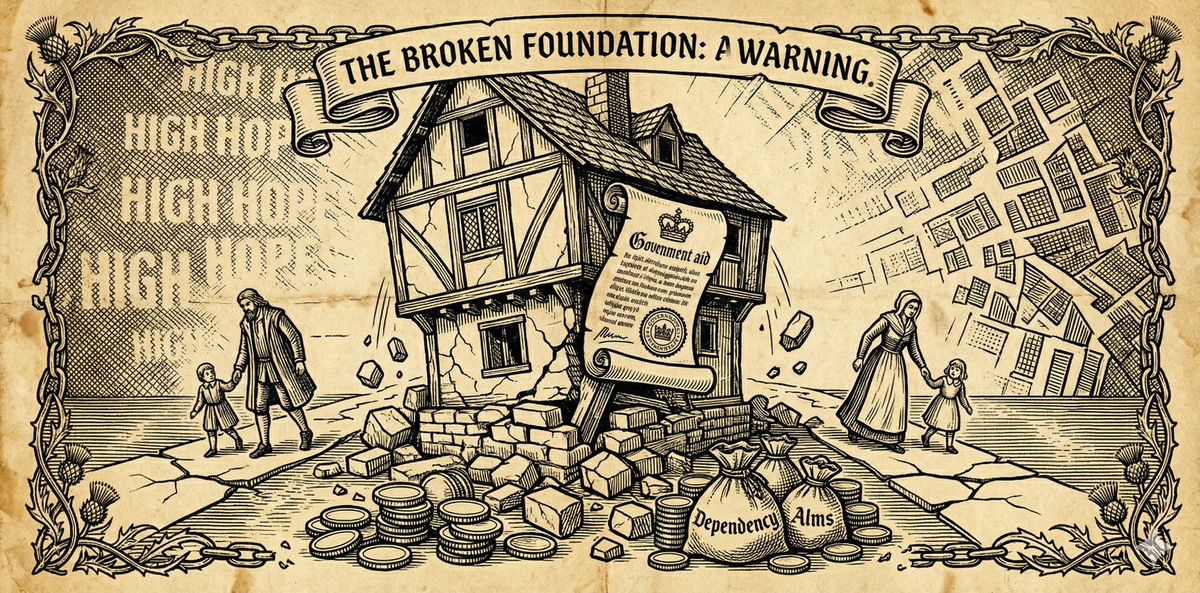

High Hopes, Fractured Families: The Great Society?

Lyndon Johnson's Great Society promised to help struggling families. Sixty years later, the data tells a different story. High hopes, fractured families.

I recently encountered a self-styled "apostle" on Instagram making an argument I had every reason to dismiss. His claimed authority was illegitimate: cessationism settled that question centuries ago, and modern self-appointed apostles are about as biblically sound as a three-dollar bill. But here's the problem: the argument he was making about black America, the Great Society, and government dependency? I couldn't dismiss it. Because the data backs it up.

This is what I wrote about a short while ago: the broken clock phenomenon. Even unreliable sources occasionally stumble into truth, not because they're suddenly credible, but because truth is objective; it doesn't care who's speaking it. And this particular broken clock had struck on an uncomfortable fact: Lyndon Johnson's Great Society programs, sold as a rescue mission for struggling black families, may have done more to disrupt black family formation than anything since Reconstruction.

There's a way that seems right to a man, Scripture tells us, but its end is the way to death. That verse is referring to a man's own spiritually deceived state, but there's a parallel in society at large. Good intentions, it turns out, don't guarantee good outcomes. Sometimes they pave the road to exactly what you were trying to prevent.

The Trajectory We Don't Talk About

Here's what we're rarely told about the century between slavery's end and the Great Society's launch: black families were rebuilding. Not perfectly, not without struggle, not at the pace most today would have preferred, but rebuilding nonetheless. The post-Reconstruction era saw black Americans reunifying families torn apart by slavery, establishing businesses, purchasing land, founding educational institutions, and building churches that became the moral and social anchors of their communities.

Thomas Sowell and Walter Williams have documented this trajectory exhaustively. Black marriage rates in the early 20th century exceeded white marriage rates. Two-parent households were the overwhelming norm. The black church, before its theological liberalization, provided structure, accountability, and a vision of human dignity grounded in the imago Dei rather than government dependence. Booker T. Washington, for all his imperfections, understood something profound: sustainable progress comes from within communities, not from bureaucrats in Washington doling out other people's money.

That older generation, as I've noted before, had the will but no way; this young generation has a way but no will. What's changed between the two eras? Among other things, decades of perverse incentive structures embedded in federal welfare policy.

When "Help" Becomes Harm

The Moynihan Report, published in 1965 just as the Great Society programs were ramping up, warned of what was coming. Daniel Patrick Moynihan saw the destabilization already beginning in urban black families and sounded the alarm. He was, predictably, ignored because his conclusions didn't fit the narrative that more government intervention was the solution.

Here's what the Great Society's welfare structure did, whether intentionally or not: it penalized marriage. A single mother could receive benefits that a married woman with an employed husband could not. The policy effectively paid women to remain unmarried and fathers to stay away. You don't have to be a sociologist to predict what happens when you subsidize single motherhood and tax marriage: you get more of the former and less of the latter. It's Economics 101, if you will, applied to family formation.

The statistics tell the story. In 1965, roughly 25% of black children were born to unmarried mothers. By 1990, that figure had climbed to nearly 70%. Today it hovers at around 75%. This isn't random social evolution; it's the predictable result of a welfare state that treats fathers as economically redundant and marriage as a luxury the poor can't afford. The family unit (God's designed structure for human flourishing, the institution that transmits values, provides stability, and teaches children what faithful commitment looks like) was systematically undermined by policies that claimed to be helping.

The Enrichment of Intermediaries

And who benefited from this arrangement? Not the families who were supposedly being helped. No, the Great Society became a jobs program for a new class of administrators, social workers, activists, and political operatives who made careers out of managing poverty rather than eliminating it. The more entrenched the dependency became, the more indispensable their positions. There's almost no incentive to solve a problem when your salary depends on its perpetuation.

This is where the folk who discovered that grievance is profitable enter the story: those who realized that victimhood can be monetized, that keeping people dependent keeps the funding flowing. They don't want self-sufficient communities; they want clients. They don't want Booker T. Washington's vision of independent black economic power; they want dependency structures that require constant management and justify ever-expanding budgets. The control mechanism mirrors historical oppression: keep people dependent, keep them voting correctly, keep them from pursuing economic independence that might threaten the system.

The greatest tragedy isn't just the policy failure; it's the way an entire generation was conditioned to view dependency as normal, to see government assistance as a birthright rather than a temporary safety net, to accept the idea that their dignity comes from what the state provides (or allows) rather than what they can build. If you're convinced you're a victim, then you become your own victimizer: trapped not by external oppression but by the internalized belief that you can't make it without someone else's intervention.

The Hard Questions We Avoid

It's easy to complain about oppression from an air-conditioned spot on the sofa. It's easy to blame historical injustice for present dysfunction when the real culprit is current policy. But here's what's harder: acknowledging that the civil rights legislation of the 1960s (however necessary the dismantling of Jim Crow laws was) came bundled with economic policies that have proven catastrophic for the very communities they were meant to serve.

The civil rights movement and civil rights legislation are not the same thing. You can celebrate the former while critiquing the latter. You can honor the courage of those who faced dogs and fire hoses while questioning whether Johnson's War on Poverty was really designed to be won. The evidence suggests it wasn't. A war that never ends is a war that serves someone's interests: just not the people supposedly being rescued.

We're now sixty years into this experiment. Three generations have grown up in a system that rewards single motherhood, punishes real fatherhood, and teaches young people that their primary relationship should be with a government check rather than a spouse. The churches that once held communities together have been displaced by social services agencies. The moral formation that came from intact families has been replaced by the chaos of fatherless homes. And the entrepreneurs and institution-builders who might have carried forward the post-Reconstruction trajectory? Many of them never emerged, because the incentive structure taught them that hustle was optional when the check arrived on the first of the month.

What Might Have Been

Here's the counterfactual worth considering: what if the Great Society had never happened? What if, instead of treating black poverty as a problem requiring federal intervention, we'd simply removed the legal barriers that prevented black economic participation and let the rebuilding continue? What if we'd trusted communities to solve their own problems, churches to provide their own safety nets, and families to make their own decisions without government bureaucrats trying to engineer outcomes?

We'll never know, of course. But we do know this: the generation that escaped slavery and Reconstruction without government assistance made measurable progress. The generation that received the full weight of Great Society "help" has seen family structures collapse, dependency deepen, and communities fragment in ways that would have been unthinkable in 1950. That's not correlation; that's causation. And pretending otherwise is just another form of the soft bigotry of low expectations: the assumption that black Americans can't build their own futures without white liberals managing the process.

The Way Forward

There's no easy fix for sixty years of perverse incentives, no magic policy that undoes three generations of learned helplessness. But acknowledging the problem is the first step. Welfare reform efforts in the 1990s showed that work requirements and time limits can push people toward self-sufficiency without catastrophic results. School choice initiatives demonstrate that families want better options for their children and will pursue them when given the chance. The black church, where it hasn't been captured by progressive theology, still provides the moral infrastructure that government programs can never replicate.

What's needed isn't more government intervention wearing a different label; it's a fundamental reorientation away from dependency and toward agency. It's teaching young people to act out their intelligence rather than their ethnicity, to see themselves as image-bearers of God with the capacity for self-determination rather than as victims requiring perpetual management. It's recovering the vision that those post-Reconstruction families had: that freedom means the right to succeed or fail on your own terms, not the guarantee of a comfortable dependence on someone else's dime.

Black is a thing, as I've said, but it is not the king. Race doesn't determine destiny; choices do. Character matters more than melanin. And the sooner we stop treating government as savior and start treating it as the limited, constitutionally bound entity it was designed to be, the sooner we might see communities rebuilt from within rather than managed from Washington.

The Great Society promised to eliminate poverty. Instead, it bureaucratized poverty, professionalized poverty, and made poverty a permanent feature of American life with a thriving ecosystem of dependents and administrators who need each other to justify their existence. That's not compassion; that's a con. And the "broken clock" on Instagram? He saw it. Even from his illegitimate position, even without the authority he claimed, he saw what too many of us have been trained not to see.

Truth doesn't need a credible messenger. It just needs someone paying attention. And the data on what Johnson wrought? It's been screaming at us for sixty years. It's time we started listening.