Ethnic Gnosticism and the Gospel: Why Skin Color Doesn't Grant Special Knowledge

Voddie Baucham's notion of ethnic gnosticism exposes the heresy of race-based epistemology. The Gospel offers unity in Christ over identity politics.

I grew up a young goof in a largely "black" family. Even then, years before the Gospel got hold of me, I never bought into the racial ethos that seemed to permeate certain corners of my world. My dad and at least a couple of his brothers had married white women (my mom is from Italy), and yet that didn't stop the regular "Us vs Them" vibes from surfacing. I'd hear the occasional machinations about getting over on "the system" and on showing up "the man" and none of it ever sat right with me.

Perhaps it was because I often attended majority-white schools, or maybe it was having a white mom—though she was more or less considered black in terms of her affectations, demeanor, and just overall adopted cultural identity. I'll admit those were likely influencing factors. But even accounting for all that, I just really always thought it wrong for people to place such emphasis on the color of skin. It seemed... off. Wrong somehow, though I couldn't have told you why. I had no sophisticated framework, no articulated philosophy—just an instinctive revulsion to the whole enterprise. Not because I was special or had some sort of insider knowledge the adults around me lacked, but because, for reasons I still don't fully understand (providence, obviously, but I'm not necessarily trying to make that the point here), that kind of thinking held no appeal for me whatsoever.

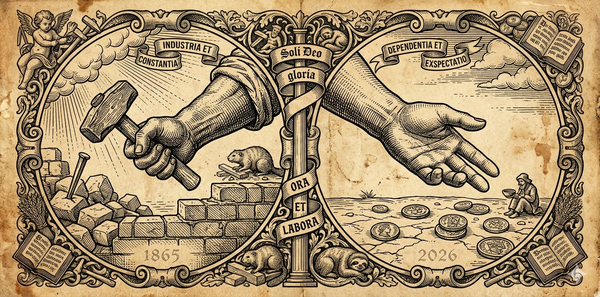

Later, as I began to mature into manhood (a far lengthier process than I care to admit), my disdain for this kind of thinking took more finite shape. I began to eschew outright any ideology that suggested there were relevant distinctions to be made between so-called majority culture and the cultures of the "subordinate" and "oppressed." The whole framework felt like a con, a way of leveraging grievance into moral authority. And in more recent years, Voddie Baucham and Dr. James White have really helped to give vent—and further articulation—to thoughts I'd held instinctively for decades.

What Ethnic Gnosticism Actually Is

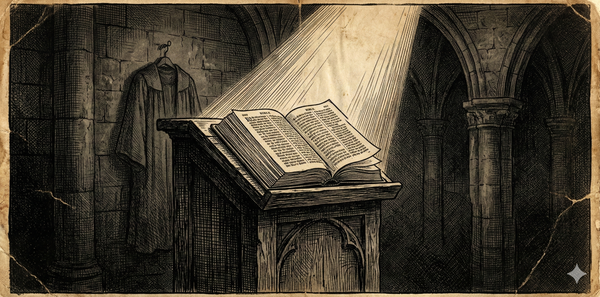

Voddie coined the term "ethnic gnosticism" to describe a very specific phenomenon: the belief that one's ethnicity grants special, secret knowledge about what is or isn't racist—knowledge that's fundamentally inaccessible to those outside that ethnic group. It's the idea that if you're black, you just know when something's racist in a way that white people can't; your melanin becomes a kind of mystical discernment tool, a racial sixth sense that operates independently of evidence, argument, or even Scripture itself.

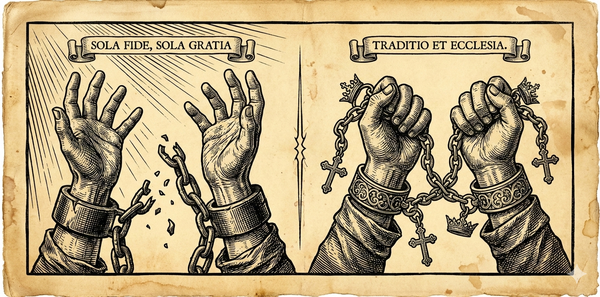

More than that, it's heresy dressed up in the language of social justice. The ancient Gnostics believed they possessed secret knowledge (gnosis) that elevated them above ordinary Christians who had to rely on Scripture and the apostolic witness. Ethnic gnosticism operates the same way: it elevates personal experience rooted in group identity above the revealed Word of God. It says, in effect, "You can't understand this because you're not one of us"—which is just another way of saying, "Scripture isn't sufficient to address this issue."

And that ought to terrify anyone who claims to be Reformed. If Scripture isn't sufficient to adjudicate questions of justice, righteousness, and human relationships across ethnic lines, then we've got a much bigger problem than racism. We've undermined the very doctrine of Scripture's own sufficiency itself.

The Secular Critique Reinforces the Point

Interestingly enough, you don't need to be a Christian to see the problems here. John McWhorter—a secular linguist and cultural critic—has spent years dismantling what he calls "wokism," and his analysis overlaps significantly with Voddie's theological critique. McWhorter argues that contemporary anti-racism has morphed into a kind of secular religion, complete with original sin (whiteness), sacred texts (Ibram Kendi, Robin DiAngelo), and an emphasis on confession and penance rather than reason and evidence.

What's particularly useful about McWhorter's framework is that it demonstrates how ethnic gnosticism isn't just theologically bankrupt; it's also intellectually bankrupt. It trades rational discourse for emotional manipulation, evidence for assertion, and individual dignity for group identity. Whether you're approaching this from a Reformed theological perspective or a classical liberal one, the conclusion is the same: ethnic gnosticism is corrosive to human flourishing and antithetical to truth.

Why the Gospel Destroys Ethnic Gnosticism

Here's where the rubber meets the road. The Gospel doesn't just critique ethnic gnosticism; it obliterates it. Galatians 3:28 is unequivocal: "There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus." This isn't a call to ignore ethnic differences or pretend they don't exist; it's a declaration that in Christ, those differences are subordinated to a greater reality—our unity in the body of Christ.

Ethnic gnosticism reverses this priority. It says your blackness (or whiteness, or whatever) is more fundamental to your identity than your union with Christ. It suggests that the most important thing about you isn't that you're a blood-bought child of God but that you belong to a particular ethnic group with a particular historical experience. And in doing so, it effectively re-erects the dividing wall that Christ tore down on the cross (Ephesians 2:14).

This may be why I was never able to stomach it as a kid...I don't know. But what I've learned since—and what I've certainly become convinced of as a Christian who's tasted true freedom rooted in Christ rather than culture—is that the Gospel offers something infinitely better than ethnic gnosticism's endless grievance economy. It offers reconciliation, not just between God and man, but between man and man. It offers a new identity that transcends race without erasing it, that acknowledges historical evil without enshrining it as the defining feature of contemporary relationships.

A Word to My Brothers and Sisters

If you're black and you've bought into ethnic gnosticism—maybe because it seemed like the only way to make sense of your experience, or because the voices promoting it were loud and confident—I'd urge you to reconsider. You don't need secret knowledge to understand racism; you need Scripture, Spirit-illumined reason, and charity toward those who may not share your experience but who genuinely want to love you as a brother or sister in Christ. Your skin doesn't make you a mystic, and it doesn't exempt you from the call to test all things and hold fast to what is good (1 Thessalonians 5:21).

And if you're white and you've been intimidated into silence by ethnic gnosticism—afraid that speaking up will get you labeled as racist, or convinced that you simply can't understand because you're not part of the "oppressed" group—let me encourage you: the Gospel gives you both the authority and the responsibility to speak truth. You don't need a black friend to give you permission to affirm what Scripture clearly teaches about justice, unity, and the sufficiency of Christ. Stand on the Word, speak with grace and conviction, and refuse to let anyone bully you into believing that your ethnicity disqualifies you from engaging these issues biblically.

Voddie Baucham gave the church a tremendous gift in naming this ideology. He helped us see that the real divide isn't between black and white; it's between those who submit to Scripture and those who subordinate Scripture to their own experience. And in an age where the latter is increasingly the norm—even within evangelical circles—we need voices willing to call it what it is: a betrayal of the Gospel, a return to Gnosticism, and a lie that must be rejected by anyone who loves Christ more than his ethnic identity.

May we be a people marked not by melanin but by the blood of the Lamb, united not by cultural affinity but by our union with Christ, and defined not by our grievances but by the grace that saved us from a far greater oppression than any we could ever suffer in this life.