The Day After Christmas: From Manger to Murder

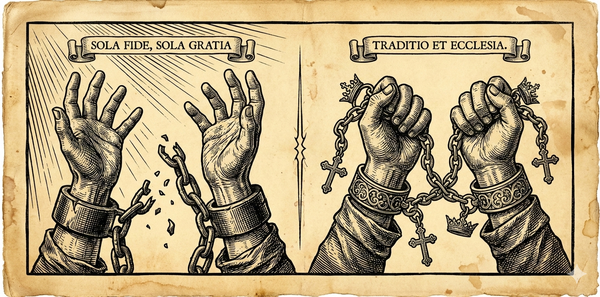

Why does St. Stephen's martyrdom follow Christmas? The Church calendar reveals Christianity's non-sentimental core: Christ came to transform, not comfort.

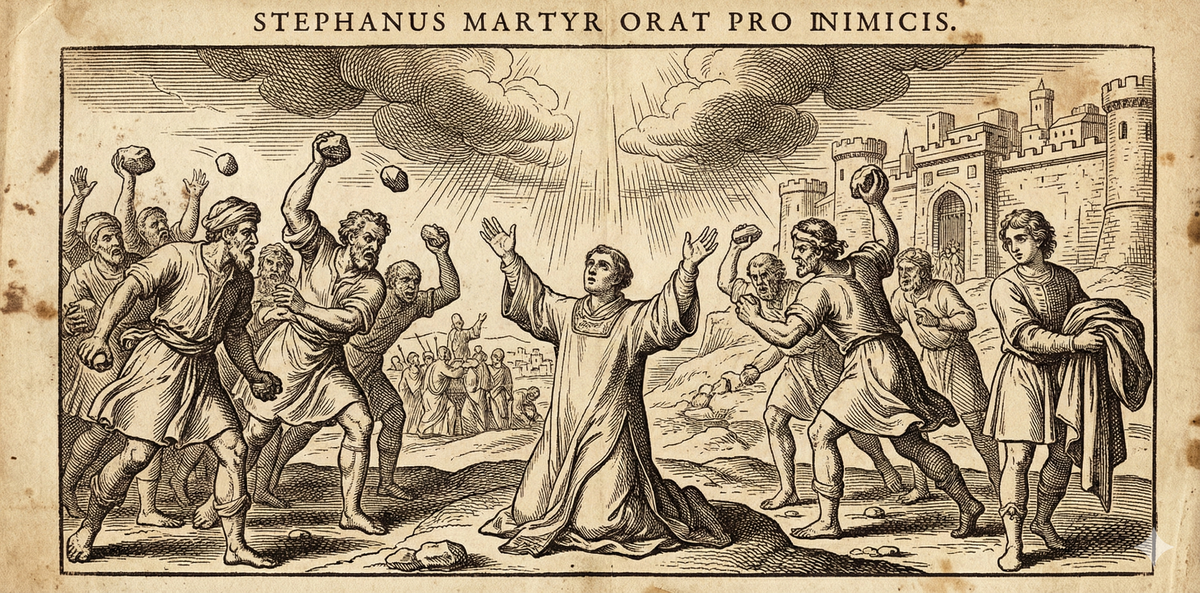

The Church calendar has a dark sense of humor. On December 25th, we celebrate the birth of the Prince of Peace, wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger—tender, vulnerable, the hope of nations made flesh. Then, precisely twenty-four hours later, on December 26th, we commemorate St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr, who was dragged outside the city gates and beaten to death with rocks while a young Pharisee named Saul held the coats of his executioners. From manger to murder. From infant Savior to adult sacrifice. The liturgical whiplash is intentional.

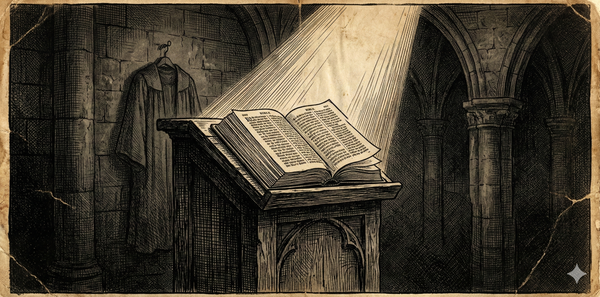

Modern Christianity, in its relentless pursuit of palatability, tends to skip over this jarring transition. We'd rather linger in the soft glow of Christmas lights than confront the blood-splattered stones of martyrdom. But the early Church knew better. They placed Stephen's feast day immediately after the Nativity not to ruin the holiday mood but to underscore a brutal theological truth: the Incarnation was never meant to be safe, comfortable, or sentimental. Christ came to divide as much as to unite—and Stephen's death is the first human echo of that divine disruption.

Stephen: The First Imitator

Stephen's martyrdom, recorded in Acts 7, is striking not just for its violence but for its deliberate parallels to Christ's crucifixion. As the stones rain down, Stephen prays: "Lord Jesus, receive my spirit"—a near-verbatim echo of Christ's final words on the cross. Then, in his last breath, he cries out, "Lord, do not hold this sin against them"—the same forgiveness Jesus extended to His killers. Stephen doesn't just die for Christ; he dies like Christ. He is the inaugural member of a long line of believers who would embody Micah 6:8 not as abstract principle but as lived—and died—reality.

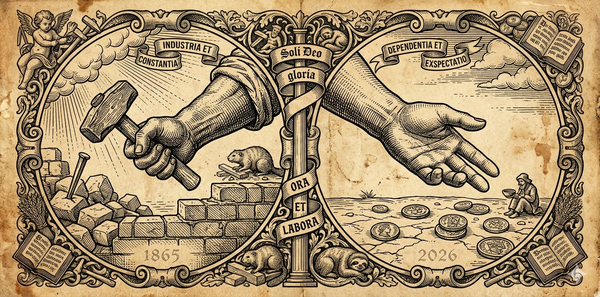

What does it mean to "act justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God"? For Stephen, it meant refusing to lie when truth-telling guaranteed death. It meant forgiving his murderers while their hands were still bloody. It meant submitting to God's sovereign will even when that will included a violent, public execution. This is Christianity stripped of its cultural varnish. This is faith without the safety net of social approval or personal comfort.

The Incarnation made such imitation possible. Before Christ, humanity had no blueprint for how to die well—how to face injustice with grace, violence with mercy, death with confidence. But once the God-man walked through suffering and emerged victorious, He left a trail for others to follow. Stephen is the first to walk it all the way to the end. His martyrdom isn't tragic; it's liturgical. It is worship enacted through willing sacrifice.

The Non-Sentimental Core of Christianity

Here's what the modern church often misses: Christianity is not primarily about making us happy, successful, or emotionally fulfilled. It is about making us holy—which frequently involves making us uncomfortable, unpopular, and (if we're really serious about it) dead. Stephen's death reveals the non-sentimental core of the faith. He wasn't killed for being a nice guy or for advocating vague moral principles. He was killed for declaring that Jesus Christ—the baby in the manger, now ascended to the right hand of God—was Lord, and that all competing claims to ultimate authority (religious, political, cultural) were fraudulent.

That message hasn't become less offensive over the centuries; we've just gotten better at softening it. We talk about Jesus as a "personal Savior" or a "life coach" or a "spiritual guide"—all technically true but catastrophically incomplete. Stephen didn't die for a life coach. He died proclaiming a King whose kingdom would outlast Rome, whose truth would shatter every carefully constructed lie, whose grace would invade the world like an unstoppable flood. And the world responded the way it always responds to such claims: with violence.

The Church calendar, in its ancient wisdom, refuses to let us forget this. December 26th is a theological gut-check. If you can celebrate the Incarnation without reckoning with its implications—if the manger doesn't lead you, eventually, to the stones—then you've misunderstood what Christmas actually accomplished. God didn't send His Son to make bad people good; He sent Him to make dead people alive. And alive people, filled with the Spirit of the living God, tend to disrupt the comfortable narratives of the surrounding culture. Stephen is Exhibit A.

Micah 6:8 in the Stones

Micah 6:8 asks: What does the LORD require of you? Justice, mercy, humility. Stephen's final moments are a case study in all three.

Justice: Stephen speaks truth to power—naming sin, calling out hypocrisy, refusing to play along with the religious establishment's self-serving narratives. He knows the cost, and he pays it anyway. This is not the sanitized "speaking truth to power" of motivational posters; this is the kind of truth-telling that gets you killed.

Mercy: Even as the rocks break his bones, Stephen prays for his killers. Not a begrudging, teeth-gritted mercy, but the kind that flows from genuine love—the kind only possible for someone who has been loved by God first. He doesn't curse them, doesn't call down divine judgment, doesn't even ask God to remember their names for future retribution. He asks God to forget their sin. That's not human nature; that's grace.

Humility: Stephen submits to the will of God without demanding an explanation, without negotiating for a better outcome, without insisting on his rights as an innocent man. He walks humbly into death because he trusts the God he walks with. This is not passive resignation; it's active, confident surrender to a Sovereign whose plans are better than ours even when they include our suffering.

The Incarnation made all of this possible. Christ modeled it first; Stephen followed. And two thousand years later, the pattern holds: those who truly encounter the God-man are transformed into people who act justly, love mercy, and walk humbly—even (or especially) when it costs them everything.

The Cultural Blind Spot: Airbrushing Martyrdom

We live in an age that worships safety, comfort, and personal autonomy. The idea that following Christ might lead to suffering—not as an unfortunate side effect but as a necessary component of discipleship—is culturally incomprehensible. We've domesticated the gospel, turned it into a self-help program with religious vocabulary. We celebrate Christmas without Easter, sing about peace on earth without acknowledging the sword Christ said He came to bring (Matthew 10:34), and preach a Jesus who affirms our choices rather than transforms our hearts.

Stephen's martyrdom is an uncomfortable reminder that Christianity, when lived authentically, is inherently subversive. It claims ultimate allegiance to a King whose kingdom is not of this world—which necessarily puts it at odds with every kingdom that is of this world. The early Church understood this. They knew that confessing "Jesus is Lord" was a politically treasonous statement in a culture that demanded Caesar-worship. They knew that living according to God's righteousness would inevitably clash with the world's definitions of justice, mercy, and humility.

The day after Christmas, the Church asks us to remember: the baby in the manger grew up to be a man who promised His followers not prosperity but persecution, not comfort but crosses, not safety but swords. And the first person to take Him at His word ended up bleeding out in a pile of stones, praying for his killers with his dying breath.

The Liturgical Logic

So why does the calendar go from manger to murder so fast? Because the Incarnation was never an end in itself—it was the beginning of something far more dangerous. God became man not to validate humanity as it was but to invade it, transform it, and ultimately judge it. The baby in Bethlehem grew up to be the man on the cross, and the man on the cross rose again to become the Lord who demands everything from His followers.

Stephen understood this. He didn't die surprised or betrayed; he died expectant, confident, and forgiving. He died the way Christ died because Christ's death—and resurrection—had rewritten the script for what it means to be human. The Incarnation made martyrdom possible by making it meaningful. Before Christ, death meant defeat. After Christ, death means deliverance.

December 26th is the Church's way of saying: if Christmas leaves you unchanged, you've missed the point. The God who became flesh didn't come to make you comfortable. He came to make you Christlike. And sometimes—often—holiness looks a lot like a man being stoned to death while praying for his enemies.

That's not tragedy. That's worship.