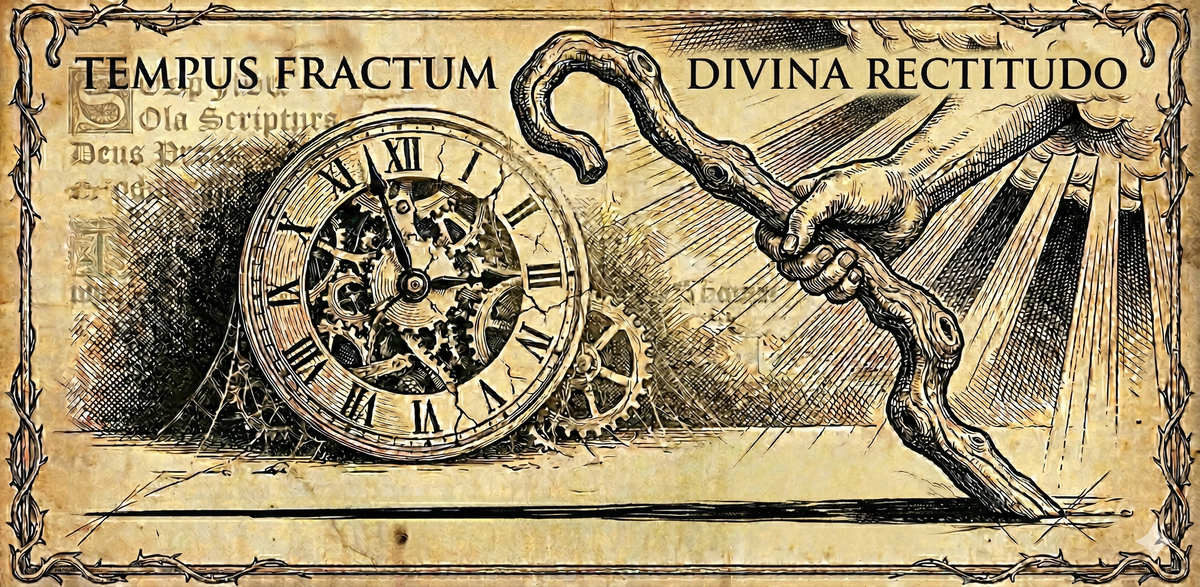

Broken Clocks & Crooked Sticks

Can truth emerge from unreliable sources? Exploring the genetic fallacy, biblical examples, and the utility of broken clocks and crooked sticks.

I recently encountered a man making excellent arguments from a position of virtually zero authority. His credentials were suspect; his theology was questionable; his claimed title was demonstrably false. And yet, the substance of what he said—about the state of culture, about the breakdown of institutions, about where we've gone wrong—rang substantially true.

This ought to create tension—though I confess it didn't much bother me at the time. His claims struck me as true despite his false spiritual credentials. But the question remains worth asking: should we reject claims simply because of their source? Or must we evaluate them on their own merits, even when the messenger lacks credibility?

It's the broken clock problem, really. Even a broken clock is right twice a day—not because it's reliable, but because the clock face happens to align with actual time at those two moments. The clock contributes nothing to the correctness of 3:15; it just happens to be stuck there when the actual time rolls around. In the same way, an unreliable source might land on truth without contributing anything to its validity.

The temptation, of course, is to dismiss everything from such sources. And there's wisdom in that skepticism—I'm not suggesting we extend credibility to those who've forfeited it. But there's a logical fallacy lurking here that we need to name: the genetic fallacy, which evaluates truth claims based on their origin rather than their validity.

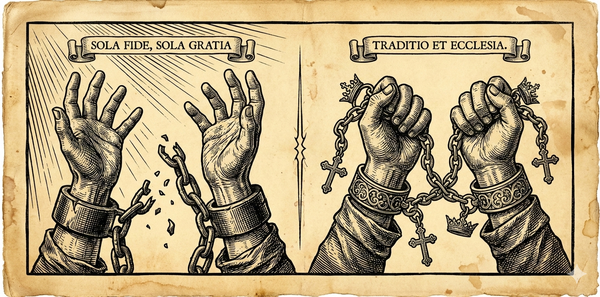

The Genetic Fallacy: When Origin Determines Truth

Here's what I mean. If a known liar tells you water boils at 100 degrees Celsius, you don't suddenly believe water boils at 50 degrees just because the source is unreliable. The claim's truth value exists independently of who makes it. The source's credibility affects our willingness to trust without verification—and that's appropriate—but it doesn't actually change whether the statement corresponds to reality.

The genetic fallacy shows up constantly in our discourse. "Well, that's just what he or she would say," as if identifying the speaker settles the question. "Consider the source," we'll mutter, as if origin determines validity. And sometimes it does—there are sources so consistently wrong that we'd be fools to trust them without extensive verification. But the fallacy lies in assuming that a claim's pedigree always determines its truth value.

Scripture actually gives us fascinating examples of this tension. Consider Balaam, the prophet for hire in Numbers 22-24. Here's a man who would sell his prophetic gift to the highest bidder, a false prophet by any reasonable standard. And yet, when God puts words in his mouth, Balaam speaks truth—real, divinely-ordained truth about Israel's future. "How can I curse those whom God has not cursed?" he asks. The prophecies he delivers are legitimate, even though the prophet himself is corrupt.

Or take Caiaphas, the high priest who orchestrated Christ's execution. John 11:49-52 tells us that Caiaphas prophesied truly—that Jesus would die for the nation—though he himself had no idea of the soteriological significance of what he was saying. He meant it as political calculation; God meant it as gospel truth. The vessel was defiled, but the message was divine.

Even the demons get this right, in their own terrified way. Mark 1:24 records them identifying Jesus correctly: "I know who you are—the Holy One of God!" Their theology is technically accurate even as their rebellion remains absolute. Truth from the mouth of evil isn't less true; it's just more jarring.

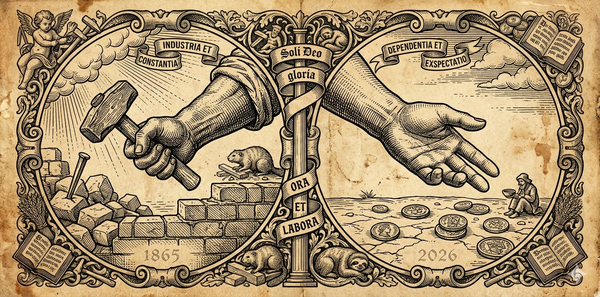

Providence vs. Coincidence: The Crooked Stick Distinction

These examples point to something deeper than the broken clock phenomenon, though. And this is where we need to make a critical distinction—one that, I hesitate to say, has occupied my thinking for quite some time.

A broken clock is accidentally right. It contributes nothing to the accuracy of the moment when appearance aligns with reality. But what God does through flawed instruments is something else entirely. He doesn't merely permit unreliable sources to stumble into truth; He deliberately uses crooked sticks to draw straight lines.

The difference is providence versus coincidence. When God uses flawed instruments—weak things, foolish things, despised things, as Paul says in 1 Corinthians 1:27-29—He's not playing broken clock roulette, hoping they'll accidentally be right twice a day. He's sovereignly orchestrating even their failures and compromises to accomplish His purposes. The stick is crooked; the line is straight; the hand guiding it all is divine.

This distinction matters because it changes how we read history and evaluate public figures. A broken clock deserves no credit for being right; it's just stuck. But a crooked stick, however flawed, is in God's hand—and recognizing that doesn't require us to baptize the stick's crookedness or pretend it's something it isn't.

Discerning Truth from Flawed Vessels

Now, this doesn't mean every flawed person through whom truth emerges is a crooked stick in the providential sense. Some sources really are just broken clocks—unreliable voices who occasionally stumble into correctness through (seeming) sheer statistical inevitability. The challenge for us, as people committed to truth, is learning to distinguish between the two categories while maintaining intellectual honesty about both.

How do we do that? Well, we start by evaluating claims on their merits rather than dismissing them wholesale based on their source. We verify. We test against Scripture and reason. We remain appropriately skeptical of those who've demonstrated unreliability, without assuming that everything they say must therefore be false. And we remember that God can draw straight lines with crooked sticks—which means we shouldn't be surprised when truth emerges from unexpected, even compromised, places.

But here's the tension we have to hold (whether inclined to or not): recognizing truth wherever we find it doesn't require us to endorse the speaker. The claim can be valid even if the claimant is not. The argument can be sound even if the arguer is suspect. And God can (and will!) accomplish His purposes through instruments that would fail any reasonable credibility test—because His sovereignty isn't constrained by our standards of reliability.

This is the framework we need if we're going to navigate a world where truth and error are mixed in the same vessels, where broken clocks occasionally tell time and crooked sticks sometimes draw straight lines. We need the discernment to evaluate claims independent of their source, the humility to recognize truth even from unexpected places, and the wisdom to know that neither validation requires us to extend unearned credibility to those who've forfeited it.

The broken clock will be right again at 3:15 tomorrow; that's just chronology. But the crooked stick in the Master's hand? That's providence and evidence of divine intent, which is a higher matter altogether.